Myopia in Singapore: A Growing Public Health Concern

By: CureQuest x MedSearch Singapore Chapter

I. Abstract

Myopia, commonly known as nearsightedness, has reached alarmingly high levels in Singapore, mainly among young children and young adults [30] . The country consistently reports some of the highest myopia prevalence rates worldwide, raising concerns about long-term visual health and associated complications [33 ] . This article explores why Singapore has become a global hotspot for myopia, examining epidemiological trends and environmental contributors such as academic pressure, screen exposure, limited outdoor activity, and urban living. Understanding these factors is essential for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies.

II. Introduction

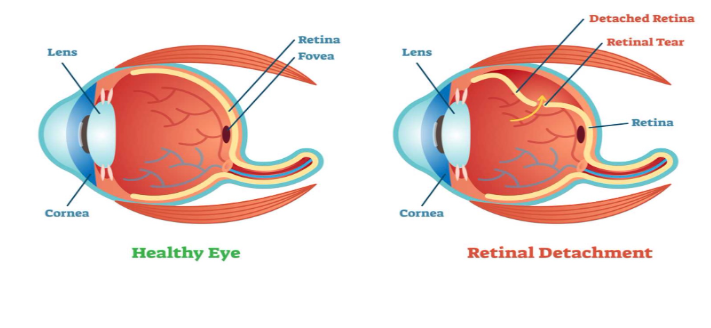

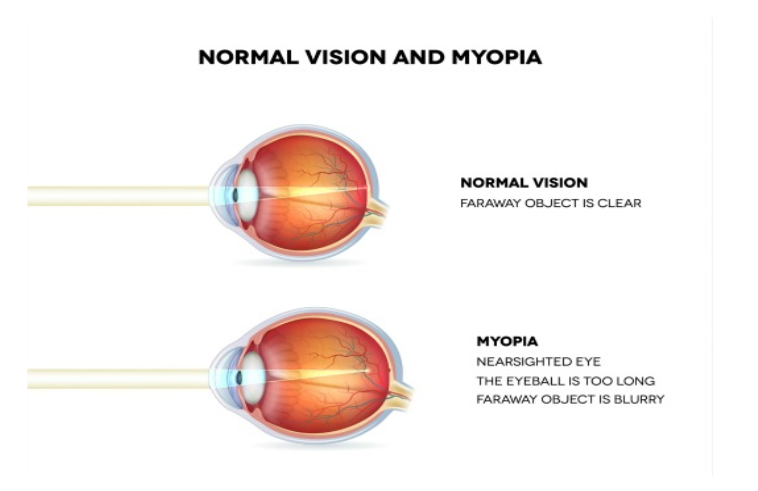

Myopia is a refractive error in which distant objects appear blurred while close objects remain clear. This condition occurs when the eye grows too long from front to back or when the cornea is excessively curved, causing light to focus in front of the retina instead of directly on it [31]. While myopia can often be corrected with glasses or contact lenses, high levels of myopia significantly increase the risk of serious eye diseases later in life, including retinal detachment, glaucoma, and myopic macular degeneration [31]. Singapore presents a unique and important case study in global myopia research. Despite its advanced healthcare system, the nation has experienced an unprecedented rise in myopia rates over recent decades [33 ]. The combination of intense educational demands, early academic pressure, widespread technology use, and a highly urbanized environment makes Singapore an ideal setting for studying environmentally driven myopia.

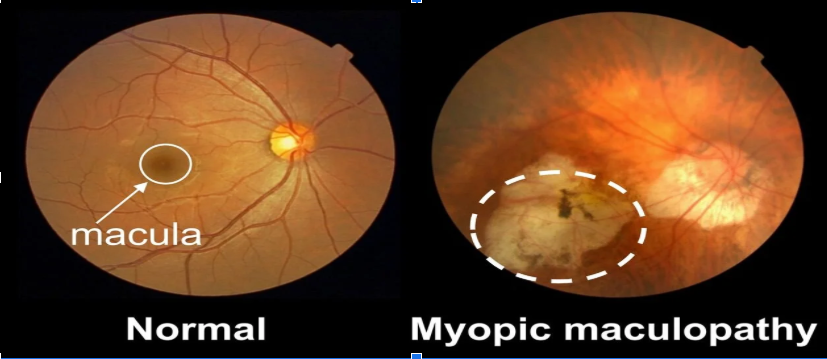

A six year study on the impact of MMD in Singaporean adults with myopia found that one in 80 myopic eyes developed MMD and one in six with existing MMD had MMD progression. [16] A paper published in 2019 by Mark Bullimore and Noel Brennan found every diopter increase in myopia is associated with an increased risk of MMD by 67%. [18]

Retinal Detachment

The stretching and thinning of the retina can also cause it to be more prone to tearing or detaching from the back of the eye, causing permanent loss of vision if not treated promptly [6].

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is characterised by a build-up of pressure in the eye causing damage to the optic nerve, resulting in vision loss. Local studies on the link between myopia and glaucoma found that likelihood of glaucoma increases with severity of myopia, with the Chinese population generally having the highest risks. For instance, Chinese with severe myopia (600 degrees) were 15 times more likely to suffer from glaucoma than one without myopia. [17]

According to Prof Aung, Singapore Eye Research Institute's executive director, researchers have yet to establish the reason for the link between myopia and glaucoma, but discoveries show the need for preventive measures. The institute suspects that the stretching of the eyeball, weakening of tissues supporting the nerve in the eye, and reduced blood flow in highly myopic eyes could be potential reasons for the development of glaucoma. [17]

Early Cataracts Development

While we hear of cataracts in elderly seniors, they can occur in children as well. Childhood cataracts are progressively increasing in prevalence over the years, occurring in up to 15 per 10,000 children. They can affect the development of vision in children and often require early treatment. Delay in treatment can result in amblyopia (lazy eye), squints (eye misalignment) or nystagmus (shaky or wobbly eyes). As the lens focuses light entering our eye, clouding of the lens in cataracts can result in blurred vision or glare. However, it may be difficult for young children to communicate that they have blurred vision. Nevertheless, some telling signs include excessive blinking and eye rubbing, squinting, covering one eye, tilting their heads or going up close to objects.

Childhood cataracts can occur from birth or develop later in childhood or adolescence. They can occur in isolation with no known cause, such as certain genetic syndromes or infections within the womb during pregnancy, or due to sustained injuries to the eye or medications (e.g. excessive steroid use). At Singapore National Eye Centre, 80% of all cataracts in children were congenital (from birth) or developmental (occur later on while growing up), and 15% are from injuries. Only one eye was affected in most cases (60%).

Additionally, the choice of treatment depends on how severe the cataracts are and how much they are affecting the child's vision. In children with mild cataracts, surgery might not be required and treatment may include glasses, eye patching (of the normal eye, to prevent lazy eye in the eye with cataract) or eye drops. However, if the cataract affects the child's vision, then surgery is required. [27]

Although statistics on myopia related cataract in Singapore remain limited, international studies like the Blue Mountains Eye Study found an increased incidence of nuclear and posterior subcapsular cataract associated with high myopia. These findings are consistent with Pan et al. , another study among Malay adults, reporting elevated incidence of PSC with severe myopia. If left untreated, the above complications can lead to irreversible vision impairment, which can significantly impact one's quality of life. Hence, early intervention of myopia is crucial in preventing these consequences in children who are studying in school and adults in the workforce. [8]

Impact on children

Surprisingly, school grades, a possible indicator of either cumulative engagement in near work activity or intelligence, were positively associated with myopia in Singapore children. [25]. This is mainly due to the fact that most children in Singapore get eyeglasses to correct their vision, thus meaning that it generally would not affect their ability to see the board in class. To support this, HPB partnered ophthalmic optics company Essilor to establish the Spectacles Voucher Fund in 2006 to ensure that lower-income parents can afford spectacles for their children. This provides students on MOE’s financial assistance schemes who require spectacles with a $50 voucher for spectacles frames and a voucher for free.

Impact on adults

The prevalent issue of myopia is also associated with significant financial burden in Singapore [23]. Its treatment methods, particularly medical interventions, such as corrective lenses, atropine eyedrops or surgeries, can impose a financial strain on individuals and healthcare systems due to their costly nature. Regular eye check-ups or prescription updates can also accumulate overtime.

In Singapore, myopia in adulthood has demonstrable consequences not only for individual visual function but also for broader economic productivity and societal burden. A population-based cost analysis from the Singapore Chinese Eye Study, which surveyed 113 Singaporean adults aged 40 years and older with myopia, estimated the mean annual direct cost of myopia care at approximately SGD 900 (≈USD 709) per person per year, with lifetime per capita costs increasing up to SGD 21,616 (≈USD 17,020) for individuals with extensive duration of refractive correction needs; the major contributors to these costs were spectacles, contact lenses, and optometry services, collectively accounting for roughly 65 % of total expenditures.

By extrapolating these individual costs across age-specific myopia prevalence in the national population, the study projected a total annual economic burden of approximately SGD 959 million (≈USD 755 million) in Singapore alone, underscoring that myopia imposes a substantial out-of-pocket burden on patients and, by extension, the economy [28]. To help ease the financial burden, the Ministry of Health has mentioned that Singaporeans being treated at Public Healthcare Institutions (PHIs) for myopia-control receive up to 75% subsidy for atropine eye drops prescribed by clinicians [24].

VI. Prevention & Control

In order to prevent myopia from going undetected in children, Singapore’s Health Promotion Board (HPB) screens preschool, primary, and secondary students [26] annually in schools [22] under the National Myopia Prevention Programme (NMPP) since 2001 . This is essential for early myopia detection, which allows the HPB to promptly identify the children who require further management.

Preschool students and Primary 1 (usually seven years old) students who were found to have defective vision in routine screening were referred to Refraction Clinics at the Student Health Centre, Health Promotion Board, for further assessment. Cycloplegic refraction was also made available for students who required it. Following assessments, children who required glasses were given a prescription to purchase spectacles at optical shops in the community. Children detected or suspected to have severe myopia, amblyopia or other eye conditions were referred to pediatric ophthalmologists at one of the public hospitals or to an ophthalmologist in private practice, as chosen by the parents. Students at higher educational levels were referred to optometrists in the community for further vision assessment and correction with spectacles [26].

Since the inception of NMPP in 2001, myopia prevalence rates in P1 children have decreased and stabilised at 26% in 2023, achieving HPB’s target of 30% or lower. In addition to this success, HPB monitors myopia severity levels (Low Myopia -0.5D to < -3D; Moderate Myopia -3D to < -5D; High myopia ≤ -5D) in selected Primary and Secondary schools as an indicator of myopia progression. The prevalence of low myopia in selected primary schools remained stable at 20% in 2023 compared to 19% in 2013. Over the same period, moderate myopia decreased from 9% to 7% and high myopia decreased from 3% to 2%. Similarly, in selected secondary schools, the prevalence of low myopia remained stable at 27% in 2023 compared to 28% in 2013. Over the same period, moderate myopia decreased from 20% to 18% and high myopia decreased from 11% to 7% [1]. These statistics highlight the clear success this programme has had in early myopia detection, which hence helps decrease the number of people with varying degrees of myopia.

Apart from government initiatives, individuals can reduce the risk of myopia by increasing the amount of time they spend outdoors. This includes playing sports, cycling, playing at the playground, or just simply walking in the park and enjoying nature. Research has shown that increased time spent on outdoor activities significantly reduces the risk against myopia onset. It is found that with approximately 76 minutes of outside time per day, there is a 50% reduction in the incidence of myopia. [9] This can be largely attributed to the much brighter light in outdoor environments as compared to indoor settings. A higher light intensity reaching the eyes stimulates chemical signals in the retina, the light sensitive layer at the back of the eye, allowing it to develop at an appropriate pace, preventing excessive eye elongation. Thus, it is especially important for children, whose eyes are still developing, to spend at least 2 hours outdoors daily in order to slow down the progression of myopia. [10]

While school vision screenings and increased outdoor activity play crucial roles in preventing late diagnosis and lowering the risk of myopia onset respectively, it may not be enough for all children, especially those with the genetics that speed up myopia onset, or those who are already facing rapid myopia progression. In such cases, medical interventions are necessary to further slow the progression of myopia.

One widely used myopia control method is the use of low-dose atropine eye drops of about 0.01% to 0.10%, which is prescribed by a doctor [12]. Atropine eye drops contain one active ingredient which is atropine sulfate, with other inactive ingredients such as Chitosan Hydrochloride; Edetate Disodium Dihydrate, USP; Glycerin, USP; Povidone K30, USP; Sodium Chloride, USP; Hydrochloric Acid 37% Reagent; Sodium Hydroxide 25% Solution; Water for Injection [14]. The active atropine compound in the eye drops works as a non-selective blocker of muscarinic receptors, present in the retina and sclera. Although the specific mechanism of atropine in myopia management is unknown, it is thought that atropine inhibits sclera thinning or stretching, and hence eye growth, by acting directly or indirectly on the retina or sclera [14]. These eye drops are typically used once nightly in both eyes. For myopia management, consistency is crucial, and regular daily use is what allows the medication to be effective over time [13]. However, in the event that the dose is not effective in slowing down short-sightedness, a higher dose of atropine (0.5% to 1.0%) may be prescribed [12].

A study done by Huang et al. suggests that high-dose atropine (1% and 0.5%), moderate-dose atropine (0.1%), and low-dose atropine (0.01%) showed clear effects in myopia control (all with statistically significant effect); pirenzepine, orthokeratology, peripheral defocus modifying contact lenses, cyclopentolate, and prismatic bifocal spectacle lenses showed moderate effects (all with statistically significant effect except for cyclopentolate and prismatic bifocal spectacle lenses); progressive addition spectacle lenses, bifocal spectacle lenses, peripheral defocus modifying spectacle lenses, and more outdoor activities showed weak effects (only progressive addition spectacle lenses with statistically significant effect); rigid gas-permeable contact lenses, soft contact lenses, undercorrected single vision spectacle lenses, and timolol were ineffective (all with no statistically significant effect) [15]. This highlights how atropine is the best option available for myopia control. In addition, the study also mentioned that High-dose atropine (1% and 0.5%) was significantly superior to other interventions except moderate-dose atropine (0.1%) and low-dose atropine (0.01%). [15]. However, a main flaw for atropine is that in high-doses such as 1%, it can cause blurring or near vision, and sensitivity to bright light [12]. Yet, this does not cause much issues as mentioned earlier, the eye drops are used at night. In essence, Atropine eye drops are a good current method to control myopia, but steps should still be taken to prevent it early on in childhood.

VII. Conclusion

To sum up, myopia can be caused by several factors, including genetics, a lack of outdoor play, and unnecessary near work [12], which is what makes it so common in Singapore, where children are placed under high academic pressure in an urban lifestyle. In addition, the progression to high myopia can lead to further health complications, such as early cataract development, myopic maculopathy, peripheral retinal degeneration and retinal detachment (RD), and glaucoma. Other than health complications, myopia can also place heavier financial and social burdens on individuals and families, including increased medical spending as well as reduced productivity and performance. Early prevention and intervention is therefore crucial in mitigating both the individual and societal burden of myopia. Strategies such as increasing time outdoors, adopting healthy visual habits and appropriate medical intervention can slow down myopia onset and progression. In conclusion, addressing myopia requires a multi-faceted approach involving individuals, families and the government. In order to control the escalation of myopia and following public health issues, continuous innovations and implementation of preventive and reactive measures is essential.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to MedSearch Singapore Chapter team for the thorough research and article writing in this research article.

Medsearch Singapore Chapter:

CureQuest: Ketaki Paranjape

Works Cited

Effectiveness of National Myopia Prevention Programme’s Strategies for Primary School Students (2024). Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/effectiveness-of-national-myopia-prevention-programme-s-strategies-for-primary-school-students/

leadssg. (2024, February 28). Social and Economic Burden of Myopia - Myopia Specialist Centre. Myopia Specialist Centre - Myopia Specialist Centre. https://www.myopiaspecialistcentre.com/social-and-economic-burden-of-myopia/

Naidoo, K. S., Fricke, T. R., Frick, K. D., Jong, M., Naduvilath, T. J., Resnikoff, S., & Sankaridurg, P. (2019). Potential Lost Productivity Resulting from the Global Burden of Myopia. Ophthalmology, 126(3), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.10.029

Du, Y., Meng, J., He, W., Qi, J., Lu, Y., & Zhu, X. (2024). Complications of high myopia: An update from clinical manifestations to underlying mechanisms. Advances in Ophthalmology Practice and Research, 4(3), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aopr.2024.06.003

The Long-Term Impact of Myopia: Why Myopia Control Matters. (n.d.). https://www.visioneyemax.com/blog/the-long-term-impact-of-myopia-why-myopia-control-matters.html#:~:text=Myopia%20is%20not%20just%20a,myopic%20macular%20degeneration%2C%20also%20rises.

Websites, N. (2025b, July 8). Glaucoma. nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/glaucoma/#:~:text=Glaucoma%20is%20an%20eye%20condition,not%20diagnosed%20and%20treated%20early.

What is the Long-Term Impact of Unmanaged Myopia? (n.d.). https://www.miamicontactlens.com/blog-post/unmanaged-myopia-impact

Zhu, X., & Zhu, X. (2020, June 8). Myopic maculopathy: What is it and how is it treated? Review of Myopia Management. https://reviewofmm.com/myopic-maculopathy-what-is-it-and-how-is-it-treated/

Lane, A. (2020, December 19). How outdoor time influences myopia prevention and control: A meta-analysis. Myopia Profile. https://www.myopiaprofile.com/articles/how-outdoor-time-influences-myopia-prevention-and-control-a-meta-analysis

My Kids Vision. (n.d.). All about outdoor time. https://www.mykidsvision.org/knowledge-centre/all-about-outdoor-time

HealthHub. (2023, June 22). Atropine eye drop (for Myopia Users). Ministry of Health Singapore. https://www.healthhub.sg/medication-devices-and-treatment/medications/atropine-eye-drop-for-myopia-users

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2022, December 21). Healthy eyes, clear vision. HealthHub. Retrieved December 29, 2025, from https://www.healthhub.sg/well-being-and-lifestyle/child-and-teens-health/growing-kid-healthy-eyes-clear-vision

Gee Eye Care. (2025). How often do you need to use atropine drops for myopia management? Gee Eye Care. https://www.geeeyecare.com/blog/how-often-do-you-need-to-use-atropine-drops-for-myopia-management.html

ImprimisRx. (n.d.). Atropine sulfate 0.025% PF [Product page]. ImprimisRx. Retrieved January 1, 2026, from https://www.imprimisrx.com/s/p/atropine-sulfate-0025-pf/01t5b000005xjT4AAI

Huang, J., Wen, D., Wang, Q., McAlinden, C., Flitcroft, I., Chen, H., Saw, S. M., … & Qu, J. (2016). Efficacy comparison of 16 interventions for myopia control in children: A network meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 123(4), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.010

Wong, Y., Sabanayagam, C., Wong, C., Cheung, Y., Man, R. E. K., Yeo, A. C., Cheung, G., Chia, A., Kuo, A., Ang, M., Ohno-Matsui, K., Wong, T., Wang, J. J., Cheng, C., Hoang, Q. V., Lamoureux, E., & Saw, S. (2020). Six-Year changes in myopic Macular degeneration in Adults of the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 61(4), 14. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.4.14

Local studies find link between myopia and glaucoma. (2018, October 11). SingHealth. https://www.singhealth.com.sg/news/research/local-studies-find-link-between-myopia-and-glaucoma

Haines, C. (n.d.). Why each dioptre matters | Myopia profile. https://www.myopiaprofile.com/articles/why-each-dioptre-matters

Postma, J., & Postma, J. (2020, December 23). The link between myopia & retinal detachment. Advance Eye Care Center |. https://advanceeyecarecenter.com/the-link-between-myopia-retinal-detachment/

Cataract. (n.d.). AOA. https://www.aoa.org/healthy-eyes/eye-and-vision-conditions/cataract

Lane, A. (n.d.). Frequency and prediction of myopic macular degeneration in adults | Myopia Profile. https://www.myopiaprofile.com/articles/myopic-macular-degeneration-adults-prevalence-progression

Karuppiah, V., Wong, L., Tay, V., Ge, X., & Kang, L. L. (2021). School-based programme to address childhood myopia in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 62(2), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2019144

Lim, M. C., Gazzard, G., Sim, E. L., Tong, L., & Saw, S. M. (2009). Direct costs of myopia in Singapore. Eye (London, England), 23(5), 1086–1089. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.22

Ministry of Health, Singapore. (n.d.). Arrangements beyond use of CDA to ensure teenagers can afford eye care and eyewear to prevent high myopia. https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/arrangements-beyond-use-of-cda-to-ensure-teenagers-can-afford-eye-care-and-eyewear-to-prevent-high-myopia

Saw, S. M., Cheng, A., Fong, A., Gazzard, G., Tan, D. T., & Morgan, I. (2007). School grades and myopia. Ophthalmic & physiological optics : the journal of the British College of Ophthalmic Opticians (Optometrists), 27(2), 126–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2006.00455.x

ZEISS. (2024, November 4). Spotlight on myopia in Singapore. ZEISS Myopia Insights Hub. https://www.zeiss.com/myopia/en/articles–insights/myopia-in-singapore.html

SingHealth Group, Singapore National Eye Centre (2025). Childhood Cataract. https://www.singhealth.com.sg/symptoms-treatments/childhood-cataract

ResearchGate, Professor Keerti Bhusan Pradhan (2015, April 06) Impact of Uncorrected Vision on Productivity - A study in an Industrial setting a Pair of Spectacles https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301943870

Ip, J. M., Saw, S. M., Rose, K. A., Morgan, I. G., Kifley, A., Wang, J. J., & Mitchell, P. (2008). Myopia and outdoor activity among Singapore school children. Ophthalmology, 115(10), 1839–1841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.019 PubMed

Saw, S. M., Tong, L., Chua, W. H., Chia, K. S., Koh, D., Tan, D., & Lim, S. C. (2001). Incidence and progression of myopia in Singapore Chinese school children. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 42(1), 143–149. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11100893/ PubMed

Morgan, I. G., & Rose, K. A. (2019). How genetic is school myopia? Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 62, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.09.004 SpringerLink

He, M., Xiang, F., Zeng, Y., Mai, J., Chen, Q., Zhang, J., … & Morgan, I. G. (2015). Effect of time spent outdoors at school on the development of myopia among children in China: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 314(11), 1142–1148. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2427585 PubMed

Wong, Y. L., Tsai, A. L. C., Jonas, J. B., & Wong, T. Y. (2025). Global rise of myopia and its public health implications. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 109(1), 4–10. https://bjo.bmj.com/content/109/1/4 SpringerLink

Lim, L., Gazzard, G., Sim, E. U., & Saw, S. M. (2010). Prevalence of myopia in Singaporean children: ethnic differences and environmental associations. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 94(7), 963–967. https://bjo.bmj.com/content/94/7/963 PubMed

III. Background / Epidemiology

Myopia prevalence in Singapore is among the highest recorded globally. Research indicates that a majority of adolescents and young adults in the country are myopic, with prevalence estimates exceeding 80% in some age groups [32 ]. What is particularly concerning is the early age of onset; many children develop myopia during their primary school years, allowing more time for the condition to worsen as the eye continues to grow.

Children and adolescents are the most affected populations. Early-onset myopia often progresses rapidly during the school years, especially when visual demands increase. By young adulthood, a significant proportion of individuals develop high myopia, which greatly elevates the risk of irreversible vision impairment later in life [30 ]. These trends highlight myopia not just as a common vision issue, but as a growing public health challenge.

IV. Contributing Factors

The rising prevalence of myopia in Singapore is influenced by a combination of environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors. One of the most significant contributors is the intense academic pressure placed on children from an early age[31]. Students often spend long hours engaged in near-work activities, such as reading, writing, and completing homework, which places a constant strain on the eyes and can accelerate the progression of myopia. This effect is further amplified by the widespread use of digital devices; prolonged screen time on computers, tablets, and smartphones requires sustained close-up focus, which may increase the likelihood of developing or worsening myopia.

Limited exposure to natural outdoor light is another key factor. Studies suggest that spending time outdoors can slow the onset of myopia in children, possibly due to higher light intensity and the opportunity for the eyes to focus on distant objects[34]. In Singapore, urban living environments often restrict access to open spaces, parks, and recreational areas, reducing children’s opportunities for outdoor activities and distance viewing. This urban lifestyle, combined with high-density housing and limited green spaces, contributes to the environmental pressures driving myopia.

While genetics also play a role, with children of myopic parents at higher risk, environmental and lifestyle factors appear to have a particularly strong influence in Singapore[34]. Understanding these multifactorial contributors is essential for developing effective public health strategies aimed at preventing or slowing myopia progression in Singaporean children.

V. Public Health Impact

Firstly, high myopia may increase risks to several long-term vision implications without proper intervention. [5,6,7,8]. Myopia is on the rise worldwide, and by 2050, it is estimated that half of the global population may be myopic, with nearly 10% experiencing high myopia, which can lead to complications such as retinal detachments, glaucoma, cataracts, and macular degeneration.

Myopic macular degeneration (MMD), also known as myopic maculopathy (MM) is when the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision, becomes damaged due to the progressive stretching and thinning of the retina and other underlying structures. [8]