Can Fruits Fight Bacteria? What Lemon, Guava, Pomegranate, and Cranberry Did to E. coli

Ketaki Paranjape

Abstract

This study looks into how different types of fruit extracts: lemon (Citrus limon), guava (Psidium guajava), pomegranate (Punica granatum), and cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) affect on the growth of Escherichia coli (E. coli). Agar plates with non-pathogenic E. coli were treated with filter paper discs soaked in fruit extracts. Bacterial growth was studied by measuring the zones of inhibition after 48 hours of incubation. Results showed pomegranate and guava extracts exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects, while cranberry and lemon showed moderate inhibition. Statistical analysis resulted in showing all extracts significantly reduced bacterial growth compared to the control. These results suggest that naturally occurring compounds in pomegranate and guava do have antimicrobial properties. Further research is recommended to determine the minimum concentrations and to test more species in laboratory settings.

Introduction

Naturally occurring compounds in fruits have been under study for years for their antimicrobial properties. Many fruits contain bioactive phytochemicals such as flavonoids, tannins, phenolic acids, and essential oils, which have shown bacterial inhibitory activity (Cowan, 1999). These compounds have interfered with bacterial survival by disrupting membranes, altering metabolic enzymes, or creating chemical environments that hinder microbial growth. Because these phytochemicals are widely available, inexpensive and natural, there is a growing scientific interest in using them as alternatives or complements to synthetic antibacterial medications. This is especially important due to rising antibiotic resistance.

Lemon (Citrus limon) contains citric acid, limonene, and other monoterpenes, which have shown antibacterial properties against E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus (Chabuck, 2013b). Limonene, in particular, is a monoterpene with the chemical formula C10H16 that can disrupt bacterial cell membranes, slowing down growth (Loza-Tavera, 1999).

Guava (Psidium guajava) is rich in phenolic compounds and flavonoids, and has been shown to inhibit Gram- negative bacteria like E.coli by interfering with cellular enzymes and membrane (Biswas et al., 2013). Pomegranate (Punica granatum) contains punicalagins, ellagic acid, and anthocyanins that show strong bacteriostatic effects by causing oxidative stress in bacterial cells (Kupnik et al., 2021). Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) contains proanthocyanidins, which prevent bacterial adhesion to host surfaces and reduce biofilm formation. These properties make it a natural inhibitor of urinary tract pathogens (Foo et al., 2000).

E.coli is a Gram negative, rod shaped bacteria which is commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals. While most strains are harmless, some can cause serious infections, including food poisoning, urinary tract infections, and bloodstream infections. It has a fast growth rate and availability with non pathogenic strains available as well.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern in today's world. Overuse and misuse of antibiotics have allowed many bacteria to evolve mechanisms that allow them to survive medications. As a result, researchers are increasingly interested in natural, plant-based antibacterial compounds that could enhance or replace existing antibiotics. Fruits with their powerful phytochemicals, may offer solutions that are safer, more sustainable, and less likely to contribute to resistance (SeyedAlinaghi et al., 2025).

The purpose of this study is to test the inhibitory effects of lemon, guava, pomegranate, and cranberry extracts on the growth of E.coli. By comparing the zones of inhibitions of these extracts, this study aims to find natural compounds that could be used as an alternate or complement to synthetic antibacterial medications.

Materials and Methods

Firstly, the experiment started out with the making of the fruit extracts from lemon, guava, pomegranate, and cranberry. All fruits were bought at the same place, same time to keep consistency. Four separate extracts were made so that each fruit could be tested independently. For the lemon extract, five ripe Citrus limon fruits of similar size and firmness were washed thoroughly under running water. The lemons were cut in half, and a manual citrus press was used to extract approximately 50 mL of juice. The juice was strained through two layers of sterile cheesecloth to remove pulp, seeds and other impurities. The filtrate was collected in a sterile 100 mL beaker and was labeled “Lemon extract”.

To make the guava extract, Fresh Psidium guajava were washed thoroughly and seeded. The fruit was combined with 40 mL of distilled water in a sterile blender and blended for 60 seconds. The mixture was put in sterile gauze, filtered and labeled.

Seeds were taken from a whole Punica granatum fruit. They were crushed using a sterile blender until a juice was formed. The juice was then strained in a sterile cheese cloth. The filtered juice was then set aside and labeled.

Twenty fresh Vaccinium macrocarpon cranberries were washed and blended with 40 mL of distilled water. The blend was filtered through gauze making approximately 30 mL of a bright red, semi-transparent extract. This solution was labeled.

All extracts were refrigerated. No preservatives or heat was treated to the extracts.

Twenty five sterile nutrient agar petri dishes were used as the bacterial growth medium. The plates were divided into five groups: control, lemon, guava, pomegranate, and cranberry. Each group contained 5 plates and all plates were labeled with fruit type and trial number. A non-pathogenic strain of Escherichia coli was used as the test organism. A sterile cotton swab was dipped into the E. coli suspension, rotated to remove excess liquid, and then streaked across the entire agar surface of each plate using a standard lawn technique. Twenty five filter paper disks were soaked in their appropriate solutions, 5 per group. The control was not soaked and left dry. Using 5 sterile tweezers, the filter paper disks were placed in their respective petri dishes. The petri dishes were then labeled with their trial number and extract type.

All plates were incubated for 48 hours in a temperature of 80 degrees fahrenheit. After the incubation period, bacterial growth was examined on all plates. A clear region around the filter paper treatment indicated bacterial inhibition. A transparent metric ruler was used to measure the diameter of the zone of inhibition. All measurements were entered into a data table for statistical comparison among the four fruit extracts.

After measurements were completed, all agar plates and contaminated materials were soaked in 90% ethyl alcohol for 1 hour. After disinfection, materials were disposed according to safety guidelines.

Results

Four fruit extracts: lemon, guava, pomegranate and cranberry, were tested for their antibacterial activity against E.coli. Zones of inhibition were measured in millimeters after 48 hours of incubation. Bigger zones of inhibition meant stronger antibacterial effects.

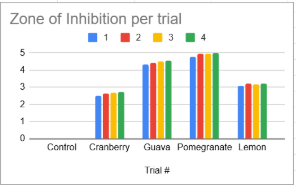

Figure 1 - Zone of Inhibition (mm) for the E-coli exposed to four various fruits (Cranberry , Guava , Pomegranate and Lemon) across 5 trials. The four colors represent the trial number. The x axis is the Various trial types and their numbers while the y axis is the zone of inhibition(mm). The control group showed no zone of inhibition.

In the control group, consisting of only a dry petri dish, no zone of inhibition was observed in any of the 5 trials. All of the control plates showed bacterial growth. This shows that E.coli was unaffected when no phytochemicals of fruits were present.

The cranberry extract showed the weakest antibacterial activity of all fruits tested. Across all 5 trials we can see cranberry extract showed the lowest inhibition. While the zones were present, many were faint or difficult to distinguish from the surrounding bacterial lawn, suggesting only mild antibacterial activity. This aligns with previous research that cranberry involves anti-adhesion of urinary pathogens rather than strong direct inhibition of bacterial growth.

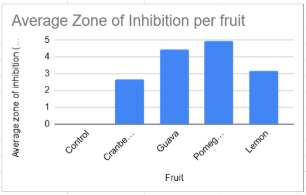

Figure 2 - Average zone of inhibition (mm) for the E-coli exposed to four various fruits (Cranberry , Guava , Pomegranate and Lemon).This graph shows the average inhibition from the five trials (trial graph above). We can see that pomegranate showed the highest zone of inhibition.

Both lemon and guava extracts demonstrated clearer and more defined inhibition zones compared to cranberry. Lemon produced inhibition zones averaging 3.167mm, and guava produced zones averaging 4.448. In both cases, the edges of the zones were defined. The inhibition produced by these two fruits was consistently visible across all trials. This shows that both contain phytochemicals capable of directly interfering with E.coli growth. Lemon’s antimicrobial effect is likely due to its citric acid and flavonoid while guavas is most likely due to tannin and flavonoids.

Of all the fruits tested, pomegranate showed the largest zone of inhibition, with an average zone of 4.906mm. The pomegranate zones were significantly larger than those produced by cranberry, lemon, or guava. This result is not surprising as pomegranate’s have high content of punicalagins, ellagic acid, and other polyphenols that are known to cause oxidative stress and membrane disruption in bacteria.

The results strongly show that pomegranate extract has the highest antimicrobial properties against E.coli out of all the fruits tested. Guava and lemon follow, while cranberry shows the lowest zone of inhibition. These results support the hypothesis that fruit extracts do have antibacterial properties.

Discussion

The results from this experiment provide a strong support for the hypothesis that fruits do have antibacterial properties. Both the guava and pomegranate showed much higher zones of inhibition with their averages. Guava showing 4.448mm and pomegranate with 4.906mm . Though all showed a zone of inhibition some were greater than others. These findings are in line with the hypothesis that fruits , mainly pomegranate and guava that are known for high levels of bioactive compounds , show greater antibacterial properties.

The zone of inhibition for the cranberries stayed pretty much in the 2mm range. This aligns with the current research that cranberries do have antibacterial properties. For example cranberry juice is a common home remedy for urinary tract infections and is helpful in preventing urinary tract infections.

Guava showed higher zones of inhibitions with the average being 4.448mm. This result is in line with current studies that claim guava has antibacterial properties. Research has shown that guava leaf extracts can inhibit the growth of both the Gram Positive and Gram negative bacterias. This is because of the presence of phytochemicals like tannins and flavonoids(Biswas et al., 2013).This is especially important because gram negative bacteria are a big public health concern as their structure makes them more likely to be antibiotic resistant(Oliveira & Reygaert, 2023).

Pomegranate extract showed the highest zone of inhibition with zones of inhibition averaging 4.906mm. This is supported by research that pomegranate extracts exhibit strong antibacterial effects against various pathogens, including E. coli . The high content of flavonoids and tannins in pomegranate contributes to its strong antimicrobial properties (Chen et al., 2020).

Lastly lemon extract made zone of inhibition with an average of 3.167mm.Though the zone of inhibition wasn't as high as guava and pomegranate, it still resulted in a pretty good zone of inhibition range.This is because lemon's has antimicrobial properties that are related to its high vitamin C content and the presence of essential oils, which have been shown to have antimicrobial effects (Rdn, 2024).

The control group which got no fruit extracts had a constant zone of inhibition rate of 0mm.This confirmed that the zone of inhibition was due to the fruits and their antimicrobial properties. These results support the hypothesis that fruit extracts that have antimicrobial properties can inhibit the growth of bacteria.

Potential limitations of this study include differences in extract concentrations and a loss of compounds in the process. Furthermore, the use of non pathogenic E.coli as the test organism may have changed the results.

The results indicate that fruit extracts contain bioactive compounds that can inhibit the growth of E.coli. Future studies could explore the specific compounds responsible for inhibition, determine minimum effective concentrations, and test more bacterial species to further evaluate the antibacterial potential of these fruit extracts.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that the null hypothesis should be rejected. The four fruits did have inhibitory potential. For all fruits a clear zone of inhibition was present. Statistical analysis of data showed that the data was statistically significant and can therefore be trusted. This proves Lemon, guava, pomegranate and cranberries inhibitory potential. Further research is recommended to test more bacterial species, and determine the concentration needed to achieve antibacterial results.

References

Biswas, B., Rogers, K., McLaughlin, F., Daniels, D., & Yadav, A. (2013). Antimicrobial activities of leaf extracts of guava (Psidium guajavaL.) on two Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive bacteria. International Journal of Microbiology, 2013, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/746165

Chabuck, N. K. K. H. a. Z. a. G. (2013b). Antimicrobial activity of different aqueous lemon extracts. japsonline.com. https://doi.org/10.7324/JAPS.2013.3611

Cowan, M. M. (1999). Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 12(4), 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.12.4.564

Chen, J., Liao, C., Ouyang, X., Kahramanoğlu, I., Gan, Y., & Li, M. (2020). Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate peel and its applications on food preservation. Journal of Food Quality, 2020, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8850339

Foo, L. Y., Lu, Y., Howell, A. B., & Vorsa, N. (2000). A-Type Proanthocyanidin Trimers from Cranberry that Inhibit Adherence of Uropathogenic P-Fimbriated Escherichia coli. Journal of Natural Products, 63(9), 1225–1228. https://doi.org/10.1021/np000128u

Kupnik, K., Primožič, M., Vasić, K., Knez, Ž., & Leitgeb, M. (2021). A Comprehensive Study of the Antibacterial Activity of Bioactive Juice and Extracts from Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peels and Seeds. Plants, 10(8), 1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10081554

Loza-Tavera, H. (1999). Monoterpenes in essential oils. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 464, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4729-7_5

Oliveira, J., & Reygaert, W. C. (2023, August 8). Gram-Negative bacteria. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538213/

Rdn, C. M. (2024, December 3). 10 reasons why you should always zest your citrus—and what to do with the leftovers. Real Simple. https://www.realsimple.com/why-you-should-zest-your-citrus-8752251

SeyedAlinaghi, S., Mehraeen, E., Mirzapour, P., Yarmohammadi, S., Dehghani, S., Zare, S., Gholami, S., Attarian, N., Abiri, A., Rad, F. F., Tabari, A., Afroughi, F., Gholipour, A., Roozbahani, M. M., & Jahanfar, S. (2025). A systematic review on natural products with antimicrobial potential against WHO’s priority pathogens. European Journal of Medical Research, 30(1), 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-025-02717-x